07/12/2020

APRA released a revised draft of its Prudential Standard CPS 511 Remuneration on 12 November 2020.

The changes in a nutshell

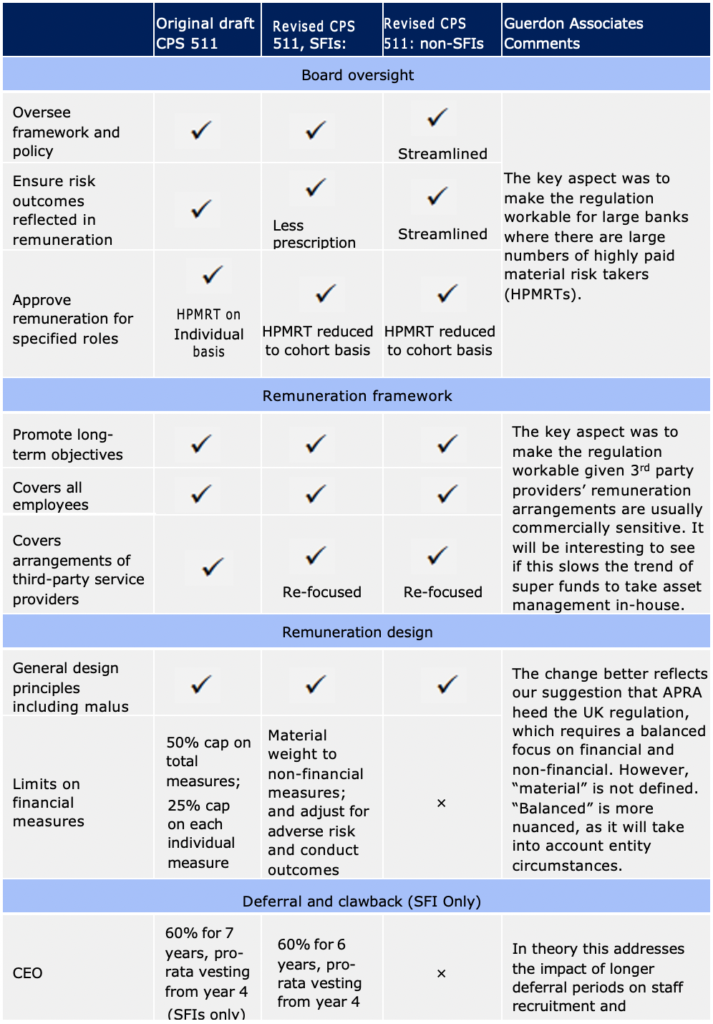

It responds to feedback on the first draft by:

- No longer prescribing a minimum weighting for non-financial measures in an incentive

- Reducing the duration of vesting and holding periods required of Significant Financial Institution (SFI) executives by one to two years

- Providing much more lenient requirements for smaller non-significantly important institutions (non SFIs)

- Reducing the scope of direct Board oversight and workload, but not accountability

APRA has maintained its focus on non-financial risks, by requiring entities to give material weight to these measures in remuneration design, rather than a prescriptive hard limit. APRA’s revised deferral requirements have been marginally reduced but not so much that it eliminates APRA-regulated entities’ competitive disadvantage in attracting talent.

Boards will not be required to approve remuneration for every highly-paid material risk taking individual. However, they may find themselves spending more time critically scrutinising management reports, since APRA considers the board accountable for the quality of management advice on remuneration outcomes.

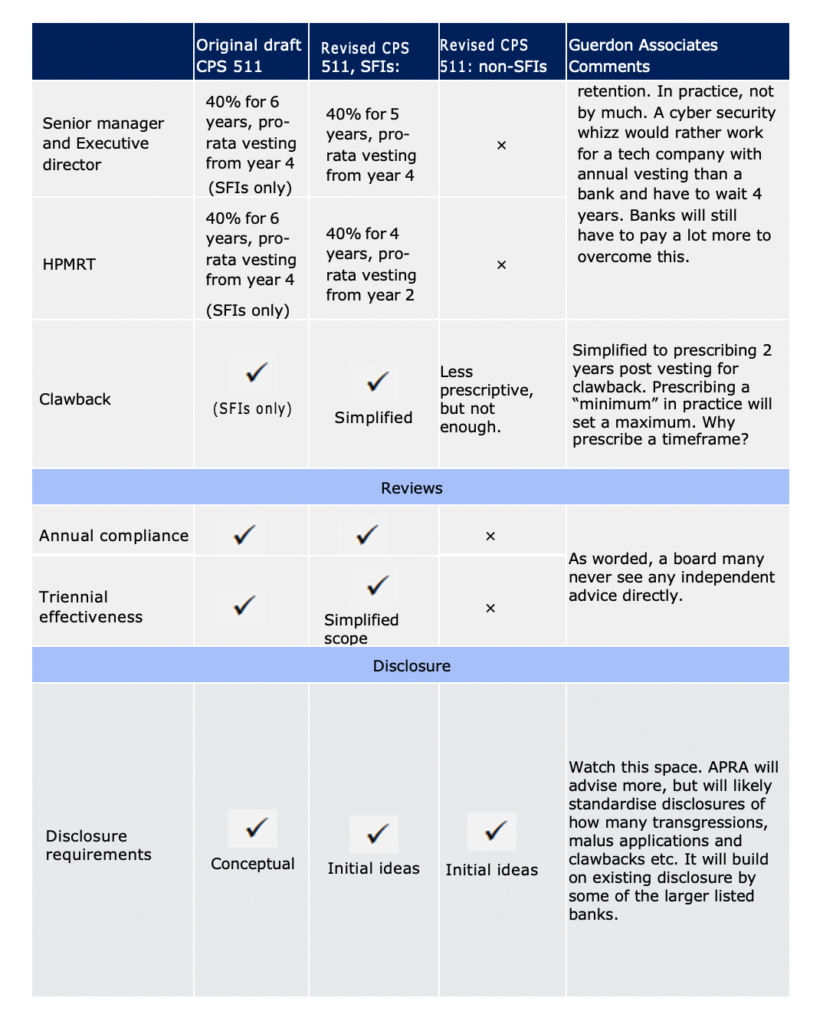

While APRA has put the hard word on boards for relying on management advice without challenge, the drafting of paragraph 33 suggests management provide the results of reviews of the remuneration framework effectiveness, and not for the board to receive the independent review itself.

Non-SFIs will not need to meet minimum deferral, clawback and review requirements under CPS 511. But someone better tell Treasury, because BEAR legislation still in force requires 40% of variable pay deferral for 4 years for smaller bank CEOs and “accountable persons”. Although we would expect FAR, in replacing BEAR, to be more consistent with CPS 511, but discrepancies are more than probable, based on prior experience.

The phased implementation timetable for CPS 511 is as follows:

- 1 January 2023: for Authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) that are SFIs (including groups headed by these SFIs).

- 1 July 2023: for insurers and RSE licensees that are SFIs (including groups headed by these SFIs).

- 1 January 2024: for all other entities (non-SFIs).

APRA requests industry feedback on the revised CPS 511 proposal, giving focus to the revision to limits on financial performance measures. The three-month consultation period ends on 12 February 2021.

An overview of changes and Guerdon Associates observations are in the below table (adapted from the APRA report) followed by a more detailed discussion.

Table 1: Changes and observations

Prescription is out, transparency is in.

With some relief, APRA has made a shift to “principles” rather than prescription. We were concerned, because while most submissions complained about the prescription, few offered viable alternatives. The change from prescribing a minimum weighting for non-financial incentive requirements to a “material” weighting is closer to the “balance of financial and non-financial requirements” of the submission Guerdon Associates submitted to the original draft. See HERE.

APRA proposes that it will require regulated entities to demonstrate publicly how they are satisfying the key principles in the standards, enhancing disclosure of outcomes. The actual disclosure requirements will not be advised by APRA until Q4 2022. This is a year after CPS 511 is in force, so entities will have to guess what data they will need to collect to comply with an unknown requirement. Those with knowledge of the difficulties associated with financial services data collection and retrieval may not relish this thought. Oh joy.

Board oversight of remuneration outcomes

Boards need only now look at executives in detail, and other highly paid material risk takers as “cohorts” and not individuals.

While some have suggested shifting the accountability for the quality of management reporting to management, in APRA’s view it is the responsibility of the board remuneration committee to provide guidance to management about appropriate reporting of information. In other words, if a board’s oversight is faulted because in good faith it relied on management advice, the board remains accountable, not management.

This concern with sheeting home the blame when things go awry fails to recognise how to manage conflicts of interest. That is, there is a conflict of interest associated with reliance on management reports on their own remuneration. APRA’s draft exacerbates the problem by suggesting that the board need never see an independent report, only a report from management on the results of an independent report (see paragraph 33).

The 50% financial cap

APRA has recognised that a hard cap on financial measures in incentives embeds scorecards as the only way to determine remuneration outcomes. Therefore, performance-based variable remuneration should give “material weight” to non-financial measures and be adjusted for adverse risk and conduct outcomes based on clearly identified risk criteria.

“Material” is not defined. There are standards applicable in the UK, Europe and US that we will reference in our submission to APRA. We trust that APRA will provide more guidance in the amended prudential practice guide (PPG 511).

The requirement for non-financial measurement does not apply to non-SFIs.

According to APRA, “at the individual level, an adjustment for adverse risk and conduct outcomes alone would not satisfy the need to give material weight to non-financial measures”. This means that the ability to reduce to zero incentive payments if it was discovered in retrospect that an executive behaved badly will not cut it. You have to state in advance what is important, measure it, and pay for it. This is consistent with prior APRA views on risk management. That is, employees should get paid extra for sound risk management, and in this case, non-financial outcomes.

Interestingly, APRA expects that there be a pre-grant assessment on non-financial performance prior to the grant of an LTI. In effect, LTIs will be squeezed and limited at the front end (probably on short term performance for annual grants) and at the back end with risk and conduct modifiers (see page 22 or APRA’s response).

On modifiers, APRA notes “to meet APRA’s requirement, many of these entities will need to strengthen their approach to more robustly apply modifiers”. We think they mean that while bank SFIs are there, insurers and super fund SFIs, and non-SFIs, have a way to go.

Non-financial measures in only one element of remuneration will also not cut the mustard, since the material weight stricture will apply to “each component of an individual’s variable remuneration, or each incentive plan”. So the proxy advisers and institutional investors who abhor non-financial measures in LTI plans had better get used to them.

APRA plans to develop a framework to help entities to determine appropriate measures in a new practice guide (CPG 511).

Deferral applicability remains illogical

Deferral applies to variable remuneration (VR). VR is defined as the amount of a person’s total remuneration that is conditional on objectives, which include performance criteria, service requirements, or the passage of time.

Salary is paid to the hour. That is, salary is service contingent. Under APRA’s definition, salary is VR. Clearly, this is not the intent.

APRA did not address the likelihood that deferral obligations will see the pay mix move to higher fixed pay, especially for entities and positions where there is no public disclosure or shareholder voting on pay. APRA will “monitor the situation”.

Deferral period reduced

APRA have reduced deferral periods. Requirements under the revised proposal are 6 years for a CEO, not 7; 5 years for senior managers and executive directors, not 6, and 4 years not 6 years for highly paid material risk takers. Percentages to be deferred have not changed.

For CEOs, pro rata vesting is allowed in years 4, 5 and 6 to align more closely with the “typical term” of Australian CEOs. For senior managers and executive directors, pro rata vesting can occur in years 4 and 5. For highly paid material risk takers, pro rata vesting can begin in year 2.

The deferral periods will still make it difficult for SFIs to attract quality recruits from other industries unless they pay a lot more. Listed SFIs will find it harder to compete with unlisted and/or overseas competitors for executive KMP, which will simply increase fixed pay.

The STI deferral includes the 12-month performance period. This resolves inconsistency with LTIs. LTI deferral also includes the performance period and any service period required.

In the practice guide, APRA intends to describe better practices relating to sign-on awards.

Partial vesting on departure will also be allowed to cover taxation at cessation.

Clawback still prescriptive

The criteria for applying clawback have been simplified. The prescription no longer has a minimum clawback period which differs for individuals depending on whether they are under investigation or not. Instead, the period has been set for at least 2 years for a range of “material” failures.

As with all regulation, specifying a minimum in effect sets the market practice maximum.

It is probably an unnecessary prescription to specify a period. The regulation specifies the application of clawback for “material” matters. Leave it at that.

Next steps

APRA has signalled an intent to finalise CPS 511 in the second quarter of 2021. Feedback will be accepted until 12 February 2021. Consultation on a prudential practice guide would occur early 2021, and consultation on draft reporting and disclosure requirements by the fourth quarter 2021.

For more information, the revised CPS 511 can be found HERE.

And the response paper HERE.

© Guerdon Associates 2024 Back to all articles

Back to all articles

Subscribe to newsletter

Subscribe to newsletter